Why Capital Project Systems Succeed or Fail

When IPA began evaluating project systems 30 years ago, the most common problem found was that projects followed no systematic common work process. Project success and failure was largely determined by particular circumstances such as the experience and expertise of the project leader. “Fixing” those systems was easy; companies developed stage-gated work process systems. Markedly better capital project outcomes resulted.

Today, although IPA still encounters the occasional project system without a decent work process, most companies embrace the gated system as a necessary ingredient in project success. However, too many companies struggle to improve their capital investments’ performance.

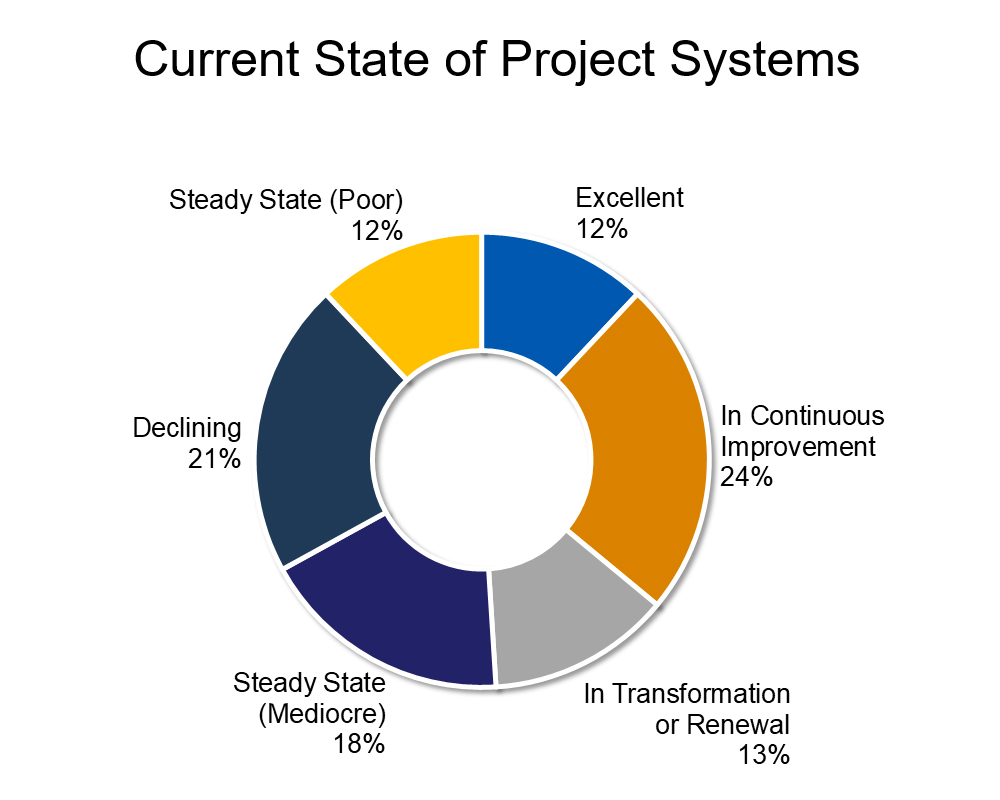

Not long ago, IPA Founder and President Edward Merrow took an in-depth look at 33 Industry Benchmarking Consortium (IBC) member companies’ project systems. IBC membership is contingent upon a company’s commitment to continuous improvement of capital processes through measuring and comparing performance metrics. Merrow found that more than half of these IBC member companies had project systems in place failed to achieve the goal of continuous improvement. As the illustration shows, either the company’s project system performance degraded over time or it had leveled out—project planning and performance was not deteriorating, but it also wasn’t getting any better.

Merrow followed up with business and project organization leaders at IBC companies included in his project systems study to find out what differentiated successful project systems with improving or excellent performance from the failing ones. In particular, he wanted to better understand what barriers stand in the way of project system improvement and how companies with successful systems overcame those barriers. From these candid interviews and based on IPA’s earlier quantitative research into project system performance, he identified four key modes of failure. Each failure mode is described below.

FAILURE MODES

#1 Organizational Traps

There are two major forms of organizational traps: highly decentralized systems and horizontally fragmented systems. Neither of these organizational models can achieve excellence.

Highly Decentralized Systems

Highly decentralized project systems lack a single (central) organization responsible for essential project system activities such as (1) hiring, training, and managing the careers of project professionals; (2) deploying project professionals to projects; (3) defining, improving, and enforcing a common work process; (4) organizing the gatekeeping process; (5) checking Front-End Loading (FEL) deliverables; and (6) measuring project system performance. In decentralized systems, most of these functions are maintained by the company’s various sites and/or business units instead.

Project system centralization does not ensure success, but a decentralized system is incapable of success. The decentralized system cannot maintain a common work process or develop a coherent career path for project professionals. A decentralized system cannot deploy resources in a rational way and cannot maintain project infrastructure such as estimating tools and databases, scheduling expertise, and controls. Improvement at one site or business unit is not easily passed on to the company’s other sites.

Horizontally Fragmented Systems

Some project systems divide various parts of the project process into separate organizations, each with its own management and each with its own turf to defend. In other words, project development and ownership (i.e., accountability) is fragmented across project development and execution.

For projects done in horizontally fragmented systems, each hand-off is an opportunity for problems. Accountability is extremely difficult to enforce, and project managers have little authority because they are essentially following the direction of each phase owner rather than taking responsibility for the project holistically.

#2 The Predictability Trap

Variability in cost outcomes is a fact of project life. But variability is dampened by excellent estimating practices and context-sensitive contingency setting. Nonetheless, even with excellent practices, considerable variability in project cost outcomes will remain. The trap arises when a project team knows it will be punished for project cost overruns. The team, reasonably, will include excess contingency in estimates, inevitably degrading competitiveness. If project teams come to rely on padded estimates to succeed, then benchmarking of competitiveness becomes the enemy. Basic project personnel competency is eroded because competence and success are progressively unrelated.

Project teams should be encouraged to prize cost estimate accuracy. Their focus should be on improving the quality of deliverables that provide the basis for the cost estimate and avoiding business or project decisions that add unnecessary risk to achieving cost targets.

#3 The Schedule Trap

For some projects, time-to-market is a paramount driver of business success. When projects have clear speed-related objectives, projects are almost always delivered on a fast schedule. Lack of speed is the single most common business complaint about capital project systems. And yet those businesses are usually part of the problem. We find the largest consumer of cycle time is FEL durations extended by unclear and changing objectives from the business. Furthermore, the desire for speed almost always means that other project outcomes suffer. Across Industry, schedule-driven projects are on average 15 percent less cost competitive than non-schedule-driven projects. Trying to consistently fix business decision-making problems by driving schedules ultimately leads to system failure.

#4 The Tick-the-Box Trap

Tick-the-box occurs when prescribed practices are followed in form rather than substance and intent, creating the illusion that projects are following good practices when in reality they are not. This is the only major trap for project systems that does not involve the businesses as part of the problem.

The tick-the-box trap occurs for a number of reasons. In some project systems, the process is seen as a substitute for competence and hard work. Following the process seemingly carries a cloak of immunity from accountability, even when decisions are made that common sense cannot support. This trap is virtually guaranteed when internal or external groups are developed to provide assurance that the process is followed rather than assessing the quality of what is produced.

In some cases, the project manager does not buy into the work process. These project managers may have been successful as a one-man show although often their experience has been confined to fairly simple large projects or smaller projects in which work process formality is not as important. In very few cases, teams that tick the box are lazy, cynical, and indifferent to the project system and project outcomes.

Assurance processes (forms of quality control) are supposed to correct the tick-the-box trap, but they often only work in the short term. Assurance processes almost immediately become bureaucratic and routine and may not even uncover all issues because personnel do not want to call out colleagues for incompetence. Ultimately, too much QC undermines accountability for quality. If work has been checked and re-checked and checked again, then it is “one of those checkers who is responsible, not me.”

Fixing the Traps

Companies face key challenges as they confront the four project system failure modes and try to drive improvement. Almost all project system managers cite resources—number and competency—as a concern. However, as necessarily distinguish between the successes and failures. In Merrow’s discussions with project system managers, systems struggling to succeed cite three key challenges:

- Generate appreciation of how projects actually work: senior management and the businesses need to be educated in the basics of projects such as what drives schedules, the role of FEL in success, and the importance of clear business objectives for projects. They also need to become familiar with what constitutes normal variation in outcomes and which project outcomes are controllable and which are not. However, attempts to educate the businesses about project work process (i.e., how to generate good projects) often do not work! Education should be tailored to the particular types of decisions the businesses make in the company that lead to poor project results (i.e., how to meet business requirements).

- Confront business management distrust for the projects organization and processes: businesses may believe the project process undermines the agility needed for business success. Project systems can be described as bureaucratic, slow, non-entrepreneurial, and risk averse. The solution to this challenge is to diagnose and discuss such misnomers. Unfortunately, the necessary in-depth conversation with the businesses usually never happens.

- Fix the governance structures that create accountability for capital: project system managers cannot solve capital governance problems. They can, however, play a very useful role in defining the governance issues for corporate management to redress.

Fixing a project system for it to be successful requires understanding and cooperation from others in the company—from corporate management, from manufacturing, and from the business management. If project system managers are going to be successful in getting that cooperation, the problem must be framed in a way that resonates with the others. That means all involved in the project systems need to see the problems from the others’ point of view.

Consider a real-life scenario in which a new project system manager joined a company with the assignment from the CEO to “do something” about the company’s absolutely poor projects. In this company, the businesses are completely opposed to “all that project process stuff.” They don’t understand it, they don’t like it, and they do not see much use for it.

The project system manager told the businesses “Every change I make will be business justified in terms that you as business leaders care about. If I put something in place and you don’t agree that it provides the business results that I promised, I will immediately withdraw it.” He then did just one thing. He installed a strong FEL 2 gate, which is the business decision gate after scope closure and development of a factored cost estimate based on conceptual design. The project system manager knew installing a real FEL 2 gate was not nearly enough to fix all the issues. But he also knew that if he installed this gate, many problems would immediately become apparent, and indeed, that is exactly what happened.

A consistent and rigorous FEL 2 gate provided an objective basis for business leaders to assess project value and to drop projects that did not make sense. And, as an added benefit, the quality of projects that got through the gate was much better. Because the project system manager was able to show business value, he obtained almost immediate moral authority to—step-by-step—put in a full gated system. And, by documenting the business justification for each element of the process, he has ensured its longevity.

Addressing the project system failure traps and key challenges to installing a project system that drives success for project systems often requires transformational change. Truly transformational change requires truly transformational leadership. As Merrow and co-author Neeraj Nandurdikar write in IPA’s latest book, Leading Complex Projects (Wiley, 2018), “In a complex project, the leader cannot demand compliance from recalcitrant stakeholders. Leadership is the art of getting full cooperation from those who are not forced to comply.” The same applies to project system leadership. A transformational project system leader understands who the stakeholders are and, crucially, what they value. Improvements are then framed in a way that explains, and measures, that value—that is, the case for change.

Complete the form below to request more information on this topic.