The Path to Better Site and Sustaining Capital Projects

Capital spent to sustain the operation of existing industrial assets is a critical element of a company’s long-term success. These site and sustaining capital projects range from simply maintaining existing operations, to improving the economics of existing operations, responding to regulations, and responding to market needs. Because existing assets in most industrial sectors are aging, their upkeep and replacement makes up a significant portion of a company’s capital spend. It is no surprise then that IPA is seeing increasing interest from clients in understanding and improving project performance at existing assets.

Where Do Site and Sustaining Capital Projects Go Wrong?

Whether the focus is growth or simply maintaining the status quo, effectively deploying site-based projects requires a significant effort. Investing in improved capital delivery at existing assets is a sound decision—companies can directly influence and control how effectively they deploy capital, which is in direct contrast with their ability to influence or predict future markets. IPA’s recent look at the capital deployment effectiveness of over 4,500 projects in several industrial sectors executed at multiple manufacturing sites highlighted a significant decline and identified the associated root causes.[1] Addressing these root causes is probably the most sound and future‑proof investment a company can make.

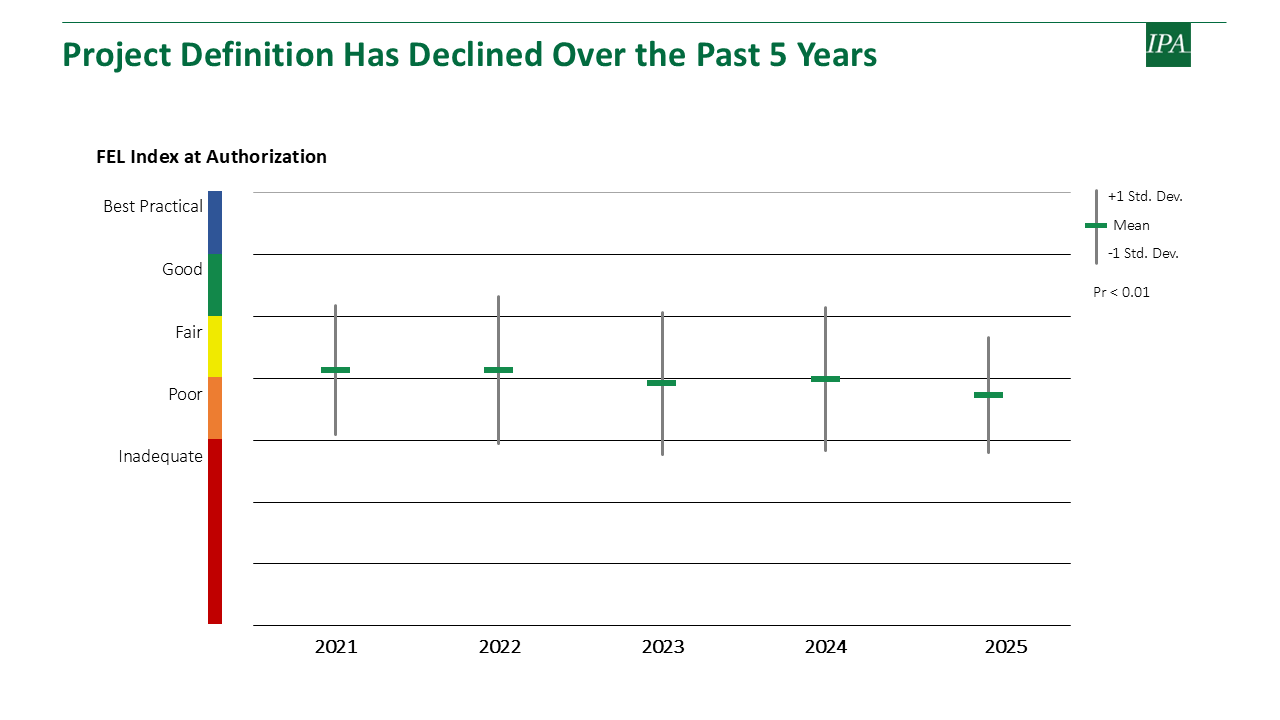

The most concerning area of decline is in the quality and completeness of Front-End Loading (FEL), the process by which project teams translate the business case into a scope of work and then into a project that is ready to execute. IPA’s measure of project definition, the FEL Index,[2] has worsened in the last 5 years. Moreover, although the average index was between Fair and Poor over the last 4 years, this year’s average FEL Index is well within the Poor range (Figure 1).

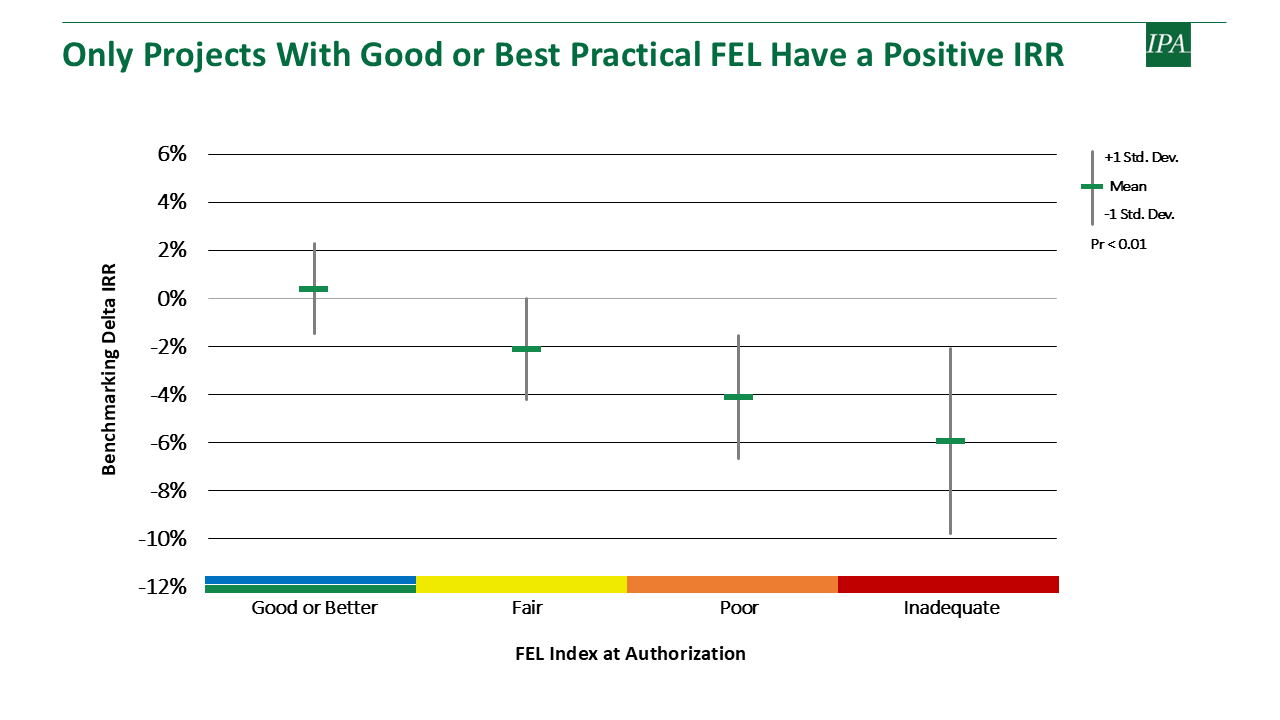

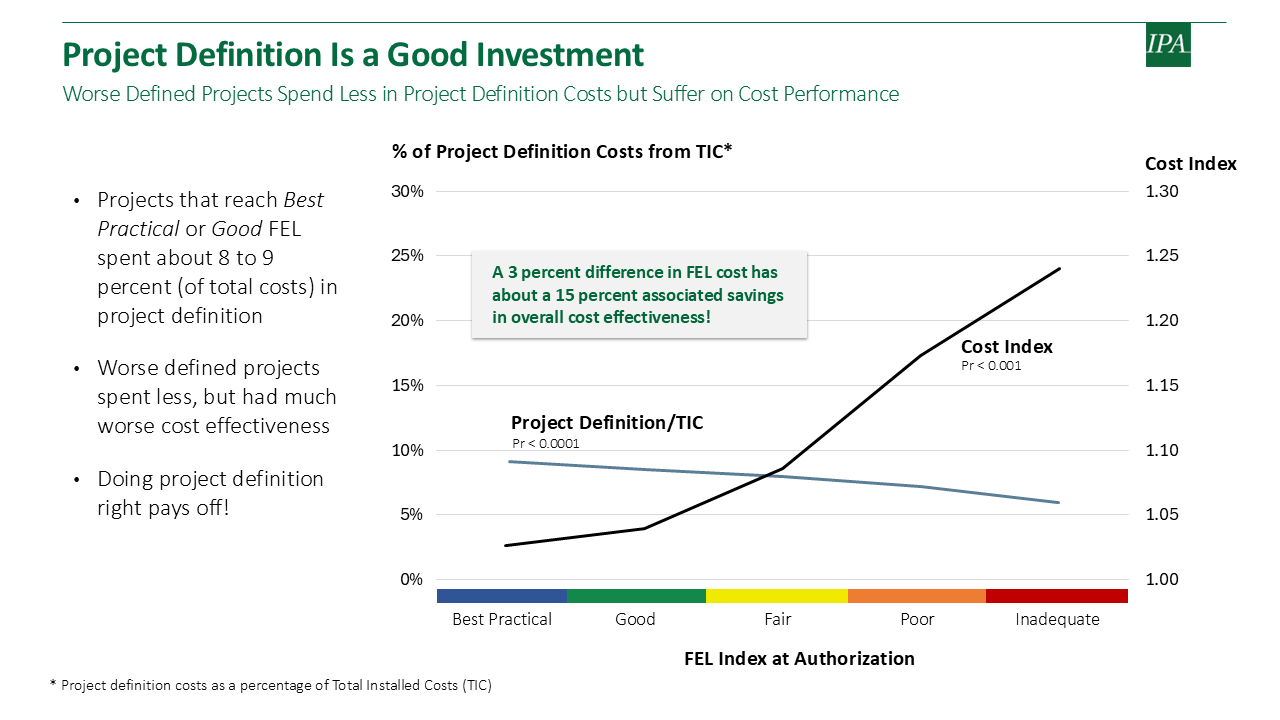

This decline is concerning, because a project’s level of definition at the start of execution affects all of the economically important performance measures—including cost, schedule, and operational performance. In fact, we find that only projects that achieve Good or Best Practical FEL have a positive internal rate of return (IRR); for every category below Good, projects lose 2 percent IRR (Figure 2).

In essence, the less FEL work completed, the more risks the project carries into execution, when resolving issues is costly and time consuming.

Project definition is a good investment because it translates into projects that are more cost effective. Based on projects in the last 5 years, projects that reach Good or Best Practical FEL are 15 percent cost effective than those that had Poor FEL. For an average portfolio of $200 million, this is $30 million in savings, which is significant.

Why Don’t We Do Better on the Front End?

Given its importance, why don’t companies do a better job on the front end for site and sustaining capital projects? Peeling back the layers behind gaps in FEL reveals three key areas: work process, governance, and staffing.

Work Process

- Common Process: Most companies that do their business through capital assets use a work process to govern the deployment of their capital. However, simply having a work process does not guarantee success. Companies that have projects routinely in the Top Quintile for FEL quality (TQ FEL) [3] used a couple of key practices around the implementation of the work process. The first one is the use of a common work process that is independent of the size and complexity of the project it’s applied to. While this may sound counterintuitive, when there is an option to use a simpler process, we find reasons to justify using it even when the project is more complex, and with time, exceptions become norms. A common work process is very usable across different project sizes and complexities: for simpler projects the deliverables and work process elements should be easier to do, but this does not mean they should not be done. There is of course a limit, and TQ FEL assets are more likely to have their major (large) projects managed by a central engineering group, allowing the asset organization to focus on the sustaining project portfolio.

- Training: To ensure the correct use of the work process, TQ FEL assets regularly train not just their own staff but also contractors and other non-owner staff who regularly contribute to projects. These sites also measure the effectiveness of the training though various tests. Focusing on familiarity and ease of use of the work process through training is important, particularly with the relatively large personnel turnover observed in recent years.

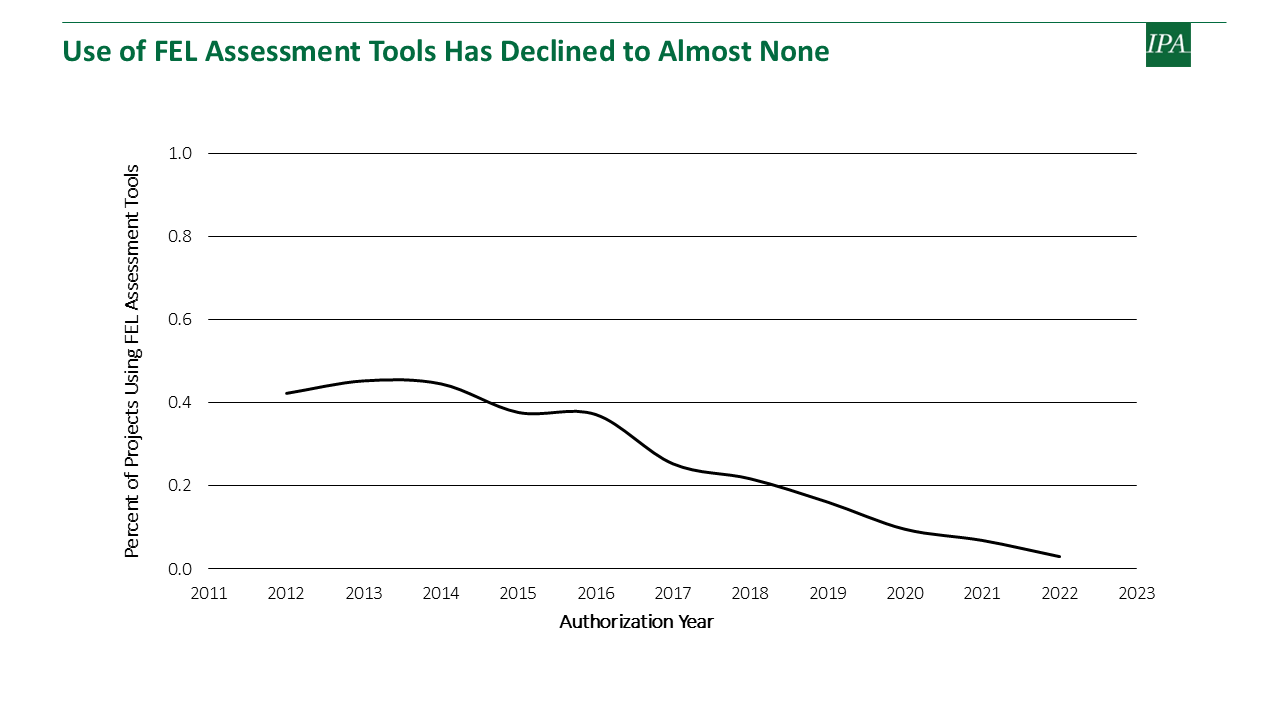

- Adherence: The last key work process practice is making sure projects adhere to the work process. TQ FEL assets don’t just mandate the use of their work process; they also ensure adherence by measuring the completeness of work process deliverables. This is often done through an assessment tool, such as IPA’s FEL Toolbox, and is ideally done through facilitation by an expert user of the tool who is independent of the project team. Unfortunately, we can see a clear decline in the use of FEL assessment tools (Figure 3). To remedy this, IPA is actively developing its , an integrated hub of self-assessment tools that aims to provide real-time information about the status of projects and more valuable insights at both the site and portfolio levels to project practitioners and system owners alike.

Governance

Effective governance, and in particular gatekeeping, is also critical to ensure adherence to the work process. While almost all the sites that we studied have documented roles and responsibilities for the gatekeepers, TQ FEL assets’ gatekeepers are better positioned to enforce adherence to the work process. These sites are more likely to formally train employees for the gatekeeping role and are more likely to base gatekeeper assignment on project size and technology to align expertise.

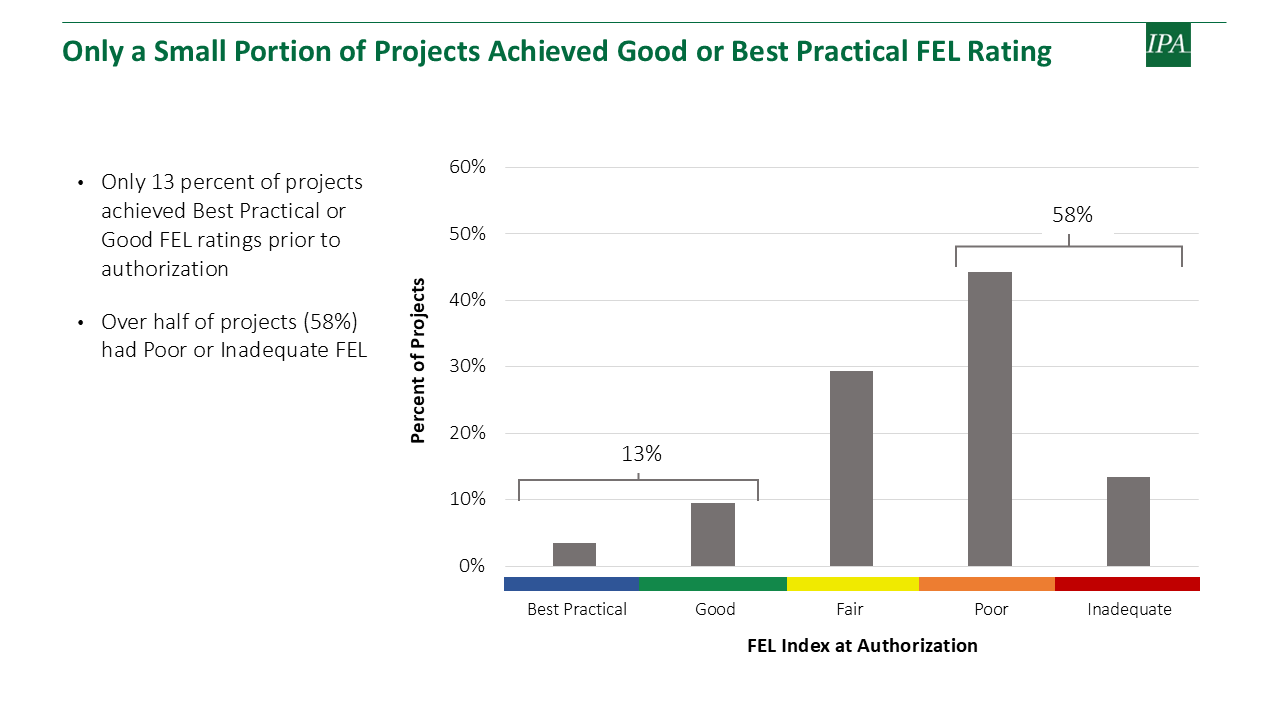

In the last 5 years, only 13 percent of projects started execution with Good or Best Practical FEL (Figure 4), which highlights an issue with the way companies enforce governance rules and closing gates for projects that have significant risks.

Staffing

Staffing project organizations is clearly a challenge across most capital-intensive industries. A company’s inability to appropriately staff projects is a clear contributor to the lack of work process adherence and often the excuse[4] for relaxation of requirements. TQ FEL assets use some key staffing practices regularly. At TQ FEL assets, project managers actually spend less time on their projects, which, at first, may seem surprising. However, they are also much less likely to fill multiple roles on the project team, which means they can focus better on managing the projects and rely on better functional support for areas where specialization (e.g., cost estimating) brings benefits to the project. In fact, TQ FEL sites had a functional competency turnover rate for estimating, controls, schedulers, construction management, and technical specialists that is two or more times less frequent than at the rest of the assets IPA looked at.

At TQ FEL assets, the project managers also have more control over their projects: they can hire non-owner staff when needed (with management approval), they are accountable for the day-to-day activities of key functions,[5] and—likely as a result—they get better functional integration and participation in key project deliverables such as the project’s schedule. The consequence of these practices is that team formation norms are consistently better for TQ FEL assets—they are significantly more likely to achieve team integration, have clear roles and responsibilities, and identify key tasks and risks to the project.

What Can Project Leaders Do?

Despite the global uncertainty around capital projects, site-based projects are here to stay. The message of our research is clear: improving our projects’ Front-End Loading quality has a strong business proposition—a 3 percent difference in FEL cost has about a 15 percent associated savings in overall cost of the project (Figure 5).

As the number and size of site and sustaining capital projects increases, there are some key practices that site leaders and project managers can use to help turn the tide on declining outcomes and practices use:

- Improve project definition quality to make sure site-based projects are well prepared for execution.

- Ensure a system-wide understanding of the work process, including the gatekeepers, and establish a way to measure adherence.

- Develop and empower project managers to drive the success of their projects through focusing on the drivers that matter for projects.

- Measure performance to understand whether improvement is taking place and aim for goals that are achievable.

The purpose of a project system is to deliver on the business promise. Focusing on these actions will enable site-based project organizations to get back to using best project practices and consistently deliver projects that meet business expectations and improve their company’s standing.

Does Your Site-Based Project System Need a Boost?

Complete the form below to start a discussion with IPA about identifying improvement opportunities for your organization.

[1] All root causes and practices described in this article have a statistical significance of Pr < 0.05 or better.

[2] IPA established a quantitative method to measure the level of definition, or FEL, on a scale that ranges from Inadequate to Best, with a Best Practical range that research shows correlates strongly with better project outcomes.

[3] Top Quintile for FEL quality projects are the top 20 percent of industry projects when ordered from best to worst FEL.

[4] We consider this an excuse because hiring staff or slowing down the project is a more beneficial approach to dealing with staffing shortages.

[5] Key functions include conceptual engineering, detailed engineering, control specialists, schedulers/planners, construction manager, and procurement.